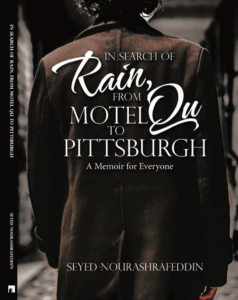

From the Publisher: “In his debut collection of nonfiction, Jim Daniels writes about trees, backyard swing sets, above-ground swimming pools, pets, and hoarding, carrying his beloved Detroit with him wherever he goes. A memoir in essays doubling as a rich and textured biography of place, An Ignorance of Trees enriches the terrain of the Midwest with heart, as bruised and beautiful as ever…”

An Ignorance of Trees is on-sale in August, but Cornerstone Press is hosting a pre-sale offer (20% off retail price) here.

Pre-Order An Ignorance of Trees “To an essential catalogue of poems, Jim Daniels adds these essays on life’s riddles and mysteries. A more than worthy work in words.” —Thomas Lynch, National Book Award Finalist

“Daniels is probably the most introspective and sensitive tough guy writing today.” —Sue William Silverman, author of How to Survive Death and Other Inconveniences

“Plain spoken and honest, grounded and vulnerable.” —Gary Fincke, author of The Darkness Call

“Daniels weaves a tapestry of worlds with beautiful insight, honesty, and grace.” —Lori Jakiela, author of All Skate: True Stories from Middle Life

Author Site About the Author: Jim Daniels is the award-winning writer of over twenty books, including Gun/Shy (2021) and The Luck of the Fall (2023). He is the recipient of fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Pennsylvania Council on the Arts, and his books have won four Michigan Notable Book Awards. A native of Detroit, he lives in Pittsburgh.

Previously on Littsburgh…

“DOGWOOD DAYS AND DOG DAYS”

Excerpted from the title essay of An Ignorance of Trees, Cornerstone Press

I know it might seem preposterous, but I sometimes wonder if our lives would have been softened somehow by a few more trees on Rome Street. If, in their shade, our cruelty to each other would not have heated up and burned into random destructive fury. We were not taught to nurture, and we did not need to be taught to destroy. Many of us seemed satisfied with random bullying and vandalism, pointless theft, drunken driving, weapons, drugs.

Our high school had no courses in tree identification or anything that explored the natural world, so after leaf collecting in grade school, our education in nature was over. Instead, we could take a class called Drugs, Delinquency, and Disorder, which attempted to meet us where we were at. That, and Outdoor Chef, which advocated for the liberal use of charcoal lighter fluid, and which proved to be very popular, both with the vo-tech crowd and the nerd-crowd. Grilling burgers and hot dogs on cement patios—we all knew it would be part of our futures.

I moved away from Rome over forty years ago, and in those years, I have had some limited success with not only identifying but growing trees. Not hugging them, but appreciating them as I begin the passage through my own final seasons. At 68, I have started counting sideways, not just up, looking to leave some greenery behind, some fruit to pick. Or at least not kill the trees I inherited. My favorite is a dogwood in the front yard of our first house in hilly Pittsburgh, the tree surrounded by green ivy running down the quick slope to the retaining wall next to the sidewalk. The previous owner had been in the Mafia, according to his surviving relatives, and had used his downtown flower shop as a front, but his wife had taken her nourishment from the yard and trees. The first year after we moved in, she sent us a Christmas card with an old photo tucked inside of the dogwood in bloom. My tree, she called it, though she never came back to visit.

Five matching windows across the front of the living room looked out onto the dogwood as it did its seasonal thing: white flowers tinged with green in spring; variegated leaves, light green on darker green, through the summer; red leaves of autumn shot into brilliance with sun on the rare clear Pittsburgh day; surprise winter ice storms, the snow wet enough to stick to branches, then freeze over into crystal. My brother-in-law Andy, a gardener for a nearby university, taught me how to trim the dead branches and thin it out every year, and I like to think I helped keep it alive.

I used to say when the tree died, we’d sell the house. Thirty-five years we lived there, and the tree continued to have nothing but good things to say. The other color the tree took on was the man-made drippings of white outdoor semi-gloss I used to paint the gutters and the soffit and facia out front. The tree survived getting mangled by my clumsy ladder placement as I squeezed between branches. It survived neighbors who had admired our tree. No one had a tree as old and beautiful on the block. It outlived the childhoods of our children, my job, the drug dealers across the street, the hoarder in the house next door. And it may outlive me, downsized like my father into a small condo a few miles from that old house on Rome. It pains me as I write this in spring to know that the dogwood is blooming now, and that I will not go back to visit.

To further cement my ignorance on the tree front—cement being my favorite comparison—we also inherited a tree in the small backyard when we bought that house, a tree that put out small red fruit we first thought were cherries. Andy, with his associate’s degree in forestry from Penn State, and his gentle humor and tolerance for my ignorance, informed us it was an ornamental crabapple. He still called it The Cherry Tree for years, even after it died—yes, I did kill that one—even after we moved away. He recommended a serviceberry tree to replace it and helped me plant it. We ate those berries when we were able to beat the birds to them. Good on cereal, and worth the effort to pick.

I wonder, am I bragging about my ignorance, as we did back on the street, mocking kids for carrying books home from school to do homework? Why were we drawn to the random destruction of all things natural, even while benefiting from the escape they offered? Was it the intoxicating lure of power? The power of the primitive? The power to prove we were as hard as those streets we walked on, as the metal cars we drove? We carried knives, flicking their blades at the air or each other’s feet. Nothing to whittle. No sharpened sticks, just the flash of blades. Our cars, urban beasts, grunted on the lone prairies without hiding places. The hard exposure of cement. No give. If trees had lights…Trees do have lights. But we need the unreliable sun to turn on those lights.

All these years later, I still wrestle with that prideful ignorance. Despite the occasional spindly tree, the two surreal green patches of Mr. B. and Crazy Eddie’s lawns back on Rome, the ragged sprays of dandelions and clover, the seasonal sprouts from pea shooters, the unchanging streetlights and fire hydrants were our redwoods and mushrooms. Markers. Trail markers to keep from getting lost on those identical streets where no one trusted anyone they didn’t already know. Due to the lack of trees, dogs fought over the sparse but permanent fire hydrants as a place to piss, to temporarily mark their territory, just like me and my brothers and our friends marked ours.

We had no rake among our yard tools—raking would have made the list of chores if we had leaves to rake. If we’d had a tree, would we have carved our initials in it? Or would we have cut it down for kicks? We were comfortable in our creosote coats, protected from the life cycle on our static streets. Strangely, despite the exception of the legendary dogwood, this ignorance of trees has followed me through life. Drop me in a car anywhere in the Detroit metropolitan area, and I’m going to easily find my way home. Put me in a city park the size of a postage stamp, and I’ll find a way to get lost.

This excerpt is published here courtesy of the author and should not be reprinted here without permission.